Lawrence

Lawrence

Brief Biography

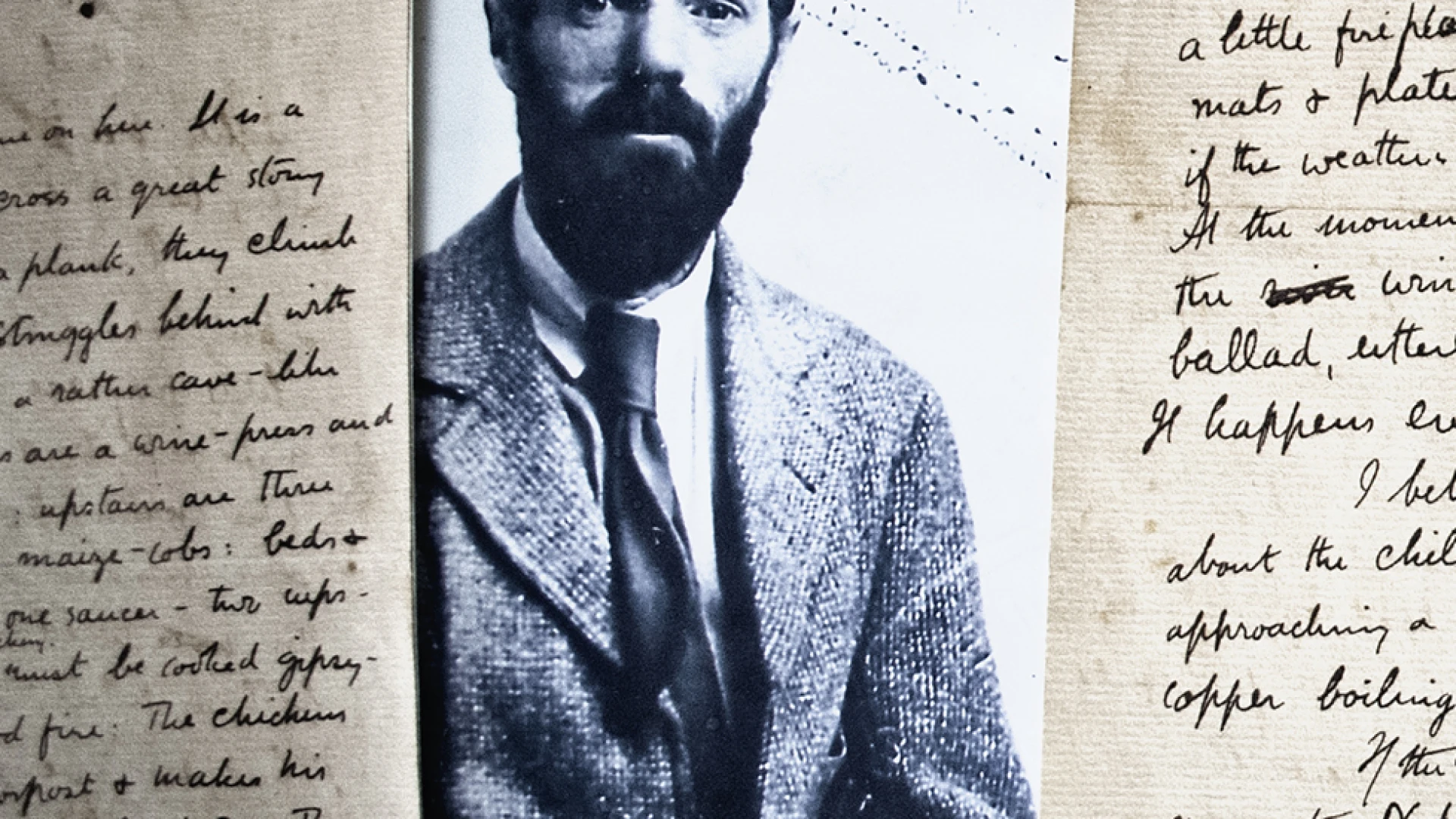

David Herbert Lawrence was born in 1885 in the English Midlands, a region described by another poet as “stupid and cruel” – a reflection of its harsh and oppressive nature. Like many third sons, he was expected to work in the mines, but a serious bout of pneumonia during his youth spared him from that fate. However, the illness left lasting damage: tuberculosis, which would accompany him throughout his life and ultimately lead to his death at the age of 45.

His mother, Lydia Beardsall, a former schoolteacher and modest poet, lacked literary ambition herself but had a crucial insight: she recognized her son’s exceptional talent. Through great personal sacrifice and careful household budgeting, she managed to save enough to nurture his love of reading. At thirteen, Lawrence won a scholarship to Nottingham High School, and through hard work, he eventually earned a degree from the University of Nottingham, beginning a career as a teacher.

His early writings caught the attention of two key figures in the literary world. One of them, Ford Madox Ford – a highly respected writer and editor of The English Review, author of one of the most important novels in English literature, The Good Soldier – saw Lawrence’s potential and published some of his work in the journal. In 1911, Lawrence placed in the hands of his dying mother the first edition of his book The White Peacock, a moment full of emotional and symbolic meaning that marked the beginning of his literary career. Soon after, he left his teaching position and decided to live by his pen.

Over the next nineteen years, he published a series of major works – including Sons and Lovers, Women in Love, and Lady Chatterley’s Lover – that earned him a lasting place in the canon of English literature. Today, many critics regard him as one of the greatest writers of the twentieth century, known for his fearless exploration of human relationships, sensuality, and the alienation of modern life.

D.H. Lawrence in Italy: An Existential and Literary Experience

D.H. Lawrence’s deep interest in Italy, combined with his unique perspective on certain cultural and natural aspects of the country, led him to write Etruscan Places, published posthumously in 1932—an authentic summa of what Italy represented to the English writer.

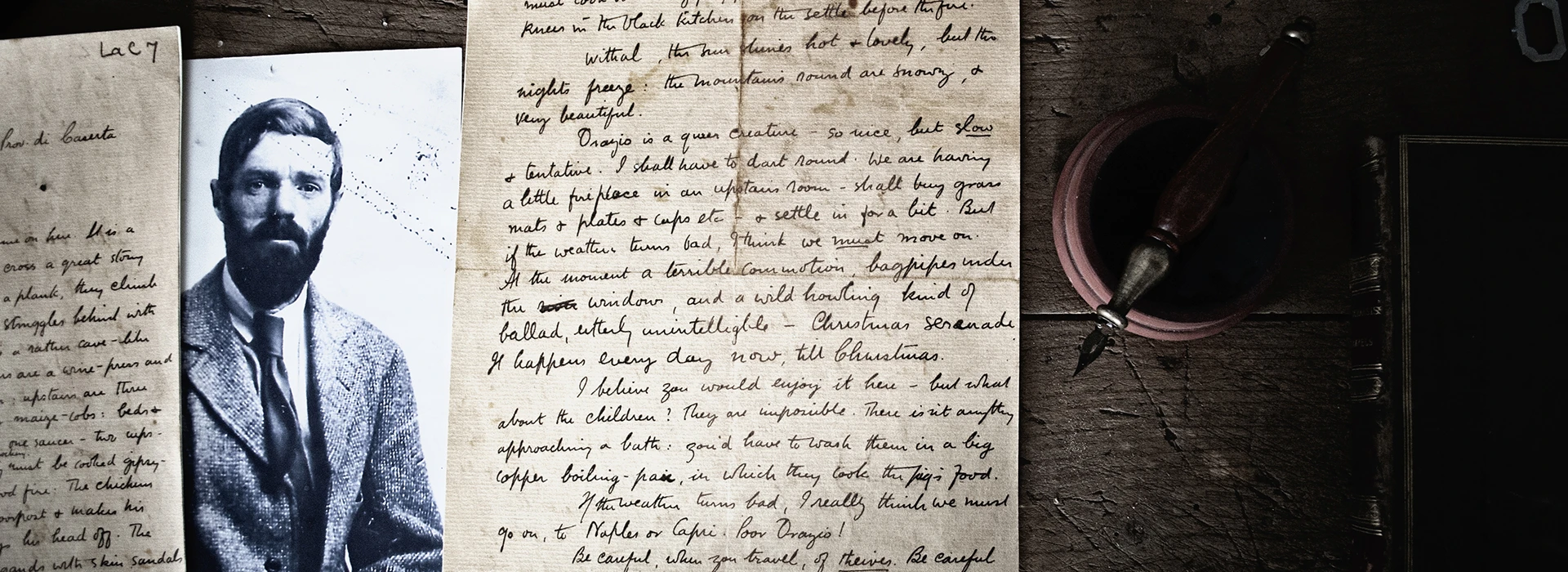

Lawrence first visited Italy in September 1912 and stayed until April 1913, living on Lake Garda. He was accompanied by Frieda von Richthofen, whom he had met in Germany earlier that year; she had left her husband and children to live with him. Lawrence arrived in Italy appalled by the industrial environment of Nottingham, which had devastated the landscape and reduced humankind to a condition of alienation akin to slavery. Suffering from tuberculosis, he had been advised to spend as much time outdoors as possible: it was during his walks that he developed a profound love for the rhythm of natural life, which became for him a kind of spiritual creed. In his vision, the universe was a living entity, with which human beings struggled to engage, seeking a deep yet painful harmony. The natural beauty of Lake Garda struck him so intensely that it caused a kind of ecstatic languor: his walks through the hills offered him direct contact with rural life, still deeply tied to nature. Lawrence perceived in Italian peasants – idealised as more “vital” and “authentic” than their English counterparts – an almost instinctive understanding of the earth’s secrets. He never forgot those sensations. Between 1920 and 1930 – the last ten years of his life, during which he also travelled to Ceylon, Australia, and North America – he spent a total of four years in Italy, and only six months in England.

After a period in Lerici, where Shelley had once lived, Lawrence returned to England in 1913, married Frieda, and gained recognition as a novelist. However, his reputation was marred by legal controversies: The Rainbow (1915), where he expressed his opposition to war, was accused of obscenity. It is no surprise, then, that after the war Lawrence and Frieda left England to embark on what became a true nomadic life. He settled in Florence, which provided the setting for Aaron’s Rod (1922), then moved to Picinisco, in the Abruzzi region – an inspiration for The Lost Girl (1920). Suffering from the harsh cold, he relocated to Taormina, from where he undertook a short but intense sea journey to Sardinia in 1921, later recounted in his travel book Sea and Sardinia (1921).

From that moment on, he began to travel the world. He narrowly escaped death from malaria in Mexico and returned to Italy in 1925. It was near Florence that he wrote his most famous, and perhaps most notorious, novel, Lady Chatterley’s Lover (1928), which brought him financial gain but also considerable bitterness. The final years of his life were marked by physical suffering, illness, and deep inner torment.

The Lost Girl and Aaron’s Rod express Lawrence’s hope that Italy might represent an alternative model to the industrial North. However, already in the early 1920s, he began to harbour doubts: he had realised that Italy, too, aspired to become a modern industrial power, much like England. In Aaron’s Rod (1922), this disillusionment is already present: Italy appears to Aaron as lacking in ideas and increasingly mechanised, reduced to a mere “commercial project”. Only in Sardinia did Lawrence feel that a remnant of the primal virility he had admired in the peasants of Lake Garda had survived. During his journey to Nuoro, he wrote that in Italy, wherever one goes, one is aware of the present, of medieval influences, and of the remote, mysterious deities of the earliest Mediterranean civilizations.

Lawrence was deeply grateful to Italy, which gave him back what he felt he had lost—like a regenerated Osiris. He visited new lands but always returned to Italy to find inspiration. In the final three years of his life, already marked by physical decline, he wrote in the poem The Ship of Death: “We are dying, we are dying, so all we can do/ is now to be willing to die, and to build the ship/ of death to carry the soul on the longest journey./ A little ship, with oars and food/ and little dishes, and all accoutrements/ fitting and ready for the departing soul”.

The lesson Lawrence learned from Italy was perhaps the hardest that each of us must learn: not how to live, but how to die.

(Based on Paolo Mattioli’s Italian translation of a lecture by Roderick Cavaliero (1928-2018), historian and former Director of the British Council in Rome).